Frontdoor: Enter

Foyer:

Take your shoes off. Get comfortable. The silverfish won't hurt you. Follow me.

Living Room:

Say hello to the man on the couch. He is life-sized but doesn't move or speak.

Stairs:

Don't go up those.

Kitchen:

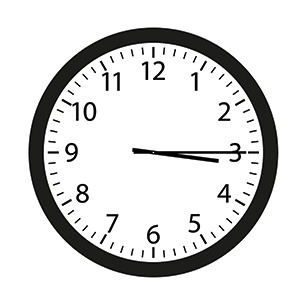

The place where things happen. Mostly in the middle of the night––you came right on time. Now that you're here, we can eat.

Sit down, says the woman who may be your mother. Where have you been? she says. Have you had a haircut? I hardly recognize you. You look different.

Uglier, your sister adds. (This is me.)

You sit at the table. There are several of us you do not recognize. You have forgotten us. You have wiped us from your memory.

Who are these people? you say.

Who are these people! says the woman who may be your mother. She spins her head around like an owl and chunks of hair fall to the ground.

She's philosophical today, says another woman.

Who are we indeed! says another.

I'm hungry, we are going to eat now, says a child.

Guestroom:

This is where the child lives. She is our cousin. She is a business woman. She is very wealthy and so we listen to her, because she pays the bills, pays for the food, pays for over-the-counter medications and under-the-counter ones.

I take the azopines and you take the triazo diazo zines. Sometimes we switch. You haven't been home in so long. You are in withdrawal. Take the green ones. Take three yellow ones. You will feel better.

Get out of my room, says our cousin, ever so sour. Close the door on your way out.

Bedroom:

We share a bedroom, you and I, because they didn't know if you were coming back and so they gave your room to Auntie Shirley. Auntie Shirley wanted two bedrooms, because she said having only one made her anxious. She needs to take more of the orangey-red pills. But she won't. She says the orangey-red pills remind her of her boyfriend who lit their house on fire.

Where's my bed? you ask, staring at the single twin bed and its sunken soiled mattress.

I knew you would ask that, I say, smiling, displaying our sisterly bond and also my teeth.

Stairs:

Nothing to see up there. Stop looking.

Bathroom:

This house has a large bathroom, with a working toilet and a bathtub and cherub wallpaper. I think of you when I look at the cherubs, because of your red round cheeks and your fat fat face.

Remember when I was fat? I ask you. I'm not anymore, I say, pulling up my shirt and showing you my stomach.

You say nothing. You stare at my rash. A grimace festers at the corners of your mouth. Your lips part in displeasure. A spider crawls out from between them.

Are you okay? I ask.

Another spider crawls out.

You're sketching me out, I say. Get some rest, have a bath. I'll run you a bath. You still like bubbles?

Bathtub:

You're having the bath of your life, aren't you? I left you alone but I'm pressing my ear to the door and listening. You're having some sort of exorcism, I think. All the bugs inside of you crawling out. This is good. You'll be fresh like tomatoes from the garden that we don't have, because none of us gardens or cares to cultivate life.

Bathtub:

I blink for one second! I spend one second blinking and you're gone! You left the tub filthy. Who knew so much filth could attach itself to a single human? You've gone up the stairs haven't you? You know what this means? Means I have to go up the stairs. You won't survive alone up there. The filth is immense. A deeper filth, one that burrows into you, in through your pores, clinging to your bones until you are diseased. And that's why I said don't go up, but you didn't listen.

You never listened before you ran away to who knows where and who knows why, and left me here alone, in this dark filth house. I'm supposed to be younger, but it's not feeling that way. I'm not ready to go up the stairs, I'm not ready, I'm not ready!

Stairs:

I mount the stairs and with each step I think of you.

It's nice to have a sister. A cousin doesn't suffice. Neither do aunts. I'm sure you noticed the aunts we've collected. We've collected several aunts in your absence and they serve us quite well, but there is no substitute for a sister.

Step, step, step. Gum sticks to my feet. I lift them with incredible effort.

The woman who may be our mother––don't worry about her, she hardly recognizes me either. Some days she calls me by your name. You see, she is already infected. Has been for a while. And that's why I'm climbing the stairs––13 more to go. To save you from the filth.

But there is no saving anyone from the filth. Not really. I thought maybe the bath would help. But spiders are only a symptom. They crawl out, but it is still inside of you. Is that why you came back? To show us? To infect us? Did you pick it up from the same place our mother did?

Second Floor:

The second floor is one bedroom, belonging to the woman who may be our mother. There is no floor, it is all covered, like soil. Filth grows upward like columns. There is so much of it.

I see one of the aunts, sprawled out on the floor. I told her not to come up. But I suppose the woman who may be our mother wanted company. She is very persuasive. She is a wild panther and her snarls move mountains. She is soft, nearly hairless, and ever so menacing.

Where are you? I call out. I will dive into the filth for you. I will scrub your bones and suck out disease like snake venom.

I step into the filth––plastic crinkles and something squishes beneath my feet. A cry cries out, I've stepped on someone, it's a rabbit, I know it. I take step after step and the filth wraps around me.

Living Room:

A strong breeze bursts the window open. Fresh air swirls around the room. The man on the couch slumps. His binding has come undone. Stuffing spills out.

Skyler Melnick is an MFA candidate for fiction at Columbia University. She writes about sisters playing catch with their grandfather's skull, boarding schools of murderous children, headless towns, and mildewing mothers. Her work has appeared in Vestal Review, Flash Fiction Magazine, Moon City Review, Gone Lawn, and elsewhere.